Board Composition and Selection

Recruiting for a Diverse Health Care Board

Practices and processes to better reflect community diversity

By Karma H. Bass

Health care governing boards have been working for years to become more diverse. Whether because of a lack of buy-in, inexperience in recruiting diverse members — or simply because they give up too soon — many boards have struggled to recruit members who appropriately represent their communities in such areas as age, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and life experience.

At the same time, the need for board diversity has never been more critical. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities emphatically demonstrates the need for a better understanding of what providing quality health care to a diverse population of patients entails.

That understanding begins in the boardroom.

Board Diversity and Quality

A more diverse set of voices around the boardroom table will better speak to the diverse needs of the communities that governing boards serve. These “voices” can infuse decision-making with invaluable perspectives and experience that are lacking in a board whose members all “look” the same — that is, same gender, ethnicity, age bracket, life experience.

Cultural insensitivity often arises from such a lack in diversity and can be a barrier to quality care for those populations that are not adequately represented; it also can keep an organization from achieving optimal quality outcomes. Raising scores for a quality indicator from the 80th percentile to the 90th percentile, for example, will be nearly impossible if improvement efforts fail to focus on segments of the organization’s patient population whose outcomes rank in the 40th percentile. As the pandemic shows, COVID-19 patients with lower quality outcomes are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities.

Rather than treating their diverse populations as a homogenous group, hospitals and health systems must do a better job of understanding how their care delivery practices affect segments of their populations differently. “We treat everyone the same” should not be the goal. A one-size-fits-all approach to health care delivery does not address the unique challenges that racial and ethnic minorities may face in seeking health care.

Addressing unnecessary readmissions, for example, means clinicians understand what might cause a patient with congestive heart failure to be noncompliant with prescriptions and more likely be readmitted. Patients may not be able to afford their medications and may not have appropriate transportation to a pharmacy to fill prescriptions or may live in a neighborhood where there is no pharmacy. Board members who have lived experience in such neighborhoods, for example, may understand these issues better and ask the types of questions that support the necessary interventions. Similarly, a board that lacks members who understand the challenges for patients navigating a complex health care delivery system when English is not their preferred language will not truly appreciate the barriers that exist.

A homogenous board will have blind spots to the diverse needs of a community. Board members with diverse life experiences, however, can shine a light on those needs and foster understanding among all members of the board.

Key Drivers of Success

Just as there is no universal approach to caring for diverse populations, there is no comprehensive diversity manual that covers the unique needs of every governing board. Each board, for instance, will need to define diversity according to the needs of its community and then develop a customized set of diversity goals.

Outlined here are several practices, processes and tools that can improve the chances of achieving a board with diversity in age, gender, race, ethnicity, life experience and perspective, among other factors. Boards that have such diversity are better equipped to address the quality needs of all their patient populations.

Diversity champion. Boards that are successful in achieving diversity typically have a champion or champions who spur the initiative and steer the process. The champion might be the hospital CEO, board chair or any member of the board who has a passion for the cause and understands the issues. The champion holds the reigns of change and doesn’t let go, continuing to reinforce the importance of recruiting members who can provider a richer understanding of community needs.

Full-board buy-in. In these times of cultural upheaval, the reason for recruiting a diverse board may seem obvious. However, every member of a governing board should be educated on why diversity matters. For example, implicit bias, the implications of health inequities, and the socioeconomic factors driving health status all are important topics for board education. It must be understood that delivering on the organization’s mission of a healthy community requires far more than clinical excellence. With this grounding, boards will be better prepared to put the imperative of board diversity in its larger context. This, in turn, builds momentum to support the arduous work of changing governance culture and practices to truly become a diverse board.

Boards can obtain buy-in through planned discussions about defining diversity, its link to quality and how the organization, its patients and the broader community will benefit from a more diverse board. Boards also should consider and agree on the new processes and other changes that will need to be implemented to achieve a diverse board. Board members, for example, should understand the importance of inclusion once a new member joins the board and be prepared to welcome new members with an understanding of how their contributions are necessary to enhance the board’s effectiveness. (See "The Importance of Inclusion" sidebar.)

Appropriate balance. Recruiting one or two board members who are female or from a minority ethnic or racial group does not constitute diversity, nor will it effect change. A study of gender diversity on corporate boards in the Harvard Business Review showed that to change board dynamics, a board must include at least three women. If only one or two members of the board (corporate boards typically consist of seven to nine members) are women, that is not enough to realize the benefits of diversity because the female members still feel like outsiders, according to the research.

Translating this finding to health care boards, which typically seat about 15 members, six to seven members should come from gender, racial, ethnic or other underrepresented populations, based on the demographic and socioeconomic makeup of the community. Governance and nominating committees should challenge themselves by setting a goal to fill vacancies only with new members who represent the agreed definition of diversity, until the board is appropriately diverse. This will not be easy. Due to the current board’s more limited social network, it may take more effort to identify diverse candidates who bring the needed competencies, but that does not mean it is impossible.

Ongoing recruitment process. Recruiting for diversity is not a one-time, quarterly or even annual endeavor that is only addressed when a board seat is vacant. Nor is it solely the responsibility of a nominating committee or board chair. Achieving diversity should be the responsibility of every member of the board. Boards should institute a rigorous, ongoing recruitment process so they have a regular list of candidates who meet the qualifications of diversity, as defined by the board. The committee should send out a call for nominations to everyone on the board at least once or twice a year. Then the committee should compile and regularly update the list.

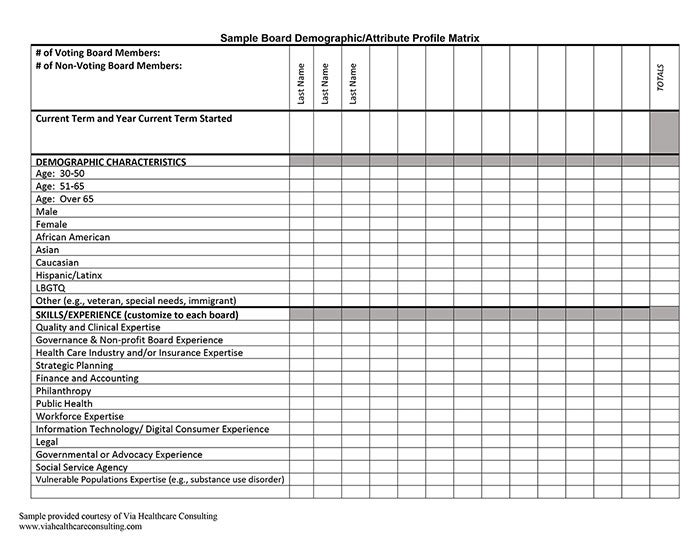

Composition/attributes matrix. A matrix-type tool can be used to display current board members’ names, ages, gender, ethnicity and the desired areas of expertise (e.g., quality/clinical, public health, human resources/workforce). Comparing current board demographics and attributes against desired demographics and attributes will help boards more easily determine the gaps in their diversity makeup and identify the qualifications needed to reach diversity goals.

Multiple sources for identifying candidates. Boards that lack diversity may not know where to search for diverse candidates. Many excellent sources are available. Patient advisory councils are good sources for candidates. These councils comprise people who have received care for themselves or family members within the hospital or health system, so they come from the community and may reflect its demographic composition. Because the councils are focused on quality, their members can offer insights on gaps in care treatment and processes that the governing board could then direct the hospital to address.

Other sources include a hospital director of community relations who has contact with key local leaders and stakeholders and can refer candidates; social service agencies, such as local chapters of United Way or Boys & Girls Clubs of America, which focus on serving those in need; and community health clinics that provide care for specific ethnic populations. Boards also could ask other community partner organizations or local leaders to suggest candidates.

Building the Future

Changing culture is challenging. But bringing in diverse voices also brings in new skills and experience that can change the board’s culture for the better. For example, according to the Harvard Business Review study on gender diversity on corporate boards, female directors contribute three advantages that men are less likely to contribute: They broaden boards’ discussions to better represent the concerns of a wide set of stakeholders; they can be more dogged than men in pursuing answers to difficult questions; and they tend to bring a more collaborative approach to leadership.

The world is changing quickly, and health care organizations must respond. Governing boards need to work now to build the board of the future, capable of identifying the diverse needs of their communities and overseeing how well their organizations are addressing those needs. Boards that are truly diverse and inclusive take the time to understand what diversity means, why it is important and the best ways to make it happen. Then, they make it happen.

Karma H. Bass (kbass@viahcc.com) is a principal with Via Healthcare Consulting and based in Carlsbad, California.

Please note that the views of authors do not always reflect the views of the AHA.