Board Composition and Selection

How to Navigate Complex, Multitiered Governance

Success comes from defining expectations for various stakeholders

By Linda Summers, Erica M. Osborne and Karma H. Bass

The rate of hospital and health system affiliations and mergers is projected to increase as organizations struggle in the aftermath of COVID-19. Although going through the process of considering affiliation, identifying a partner, undertaking due diligence and reaching agreement can be arduous, in many ways it is only the beginning of the work. After the lawyers and consultants facilitating the merger have gone home, the two organizations are left to make the marriage work, often facing significant hurdles.

Despite all this consideration, there is one area that often goes unaddressed: the actual structure and implications of the multitiered governance system resulting from the union.

In much the same way that a successful relationship between the two health care organizations takes significant effort on both sides, effective governance within the “merged” system takes intentional, thoughtful work among the separate (tiered) levels of governance and executive leadership.

Just as with organizational relationships, when governance is not effective, it is often due to unmet expectations.

Complicated Patchwork

The challenge is that most large health systems today are a complicated patchwork that:

- Were created through diverse mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures and other partnerships.

- Are stitched together through asymmetrical and differing agreements and provisions.

- Mix not-for-profit and for-profit, faith-based and secular organizations.

- Span multiple states, communities, cultures and populations.

- Deliver disparate services that span the continuum of care.

What this means for governance is that specific authorities and responsibilities of each subsidiary board within the same system may differ because of the unique terms negotiated in the affiliation agreement. These terms are in large part determined by the financial and/or strategic position of the hospital or health system that is being acquired.

For governance to be effective in a multitiered structure, key stakeholders—the executive leadership team, subsidiary boards and the system board must understand what is expected of them and what to expect from each other. How will roles change? How will decision-making authority change? How will boardroom discussion change?

Here, we outline the expectations for each stakeholder in a multitiered governance structure.

Executive Leadership

Asking a hospital board to relinquish control over what is often perceived as a large “corporate” entity can be a difficult element of a successful merger. We have seen firsthand what can happen when a local board, new to an affiliation, does not understand its new responsibilities and how they connect to the system. The board often clings to its former work, leading to confusion and at times, animosity toward the acquiring entity. Transparency is key to building trust, and thus a path to successful multitiered governance.

Creating that trust begins, ideally, pre-affiliation. This duty rests with the CEO and executive leadership team.

The role of the chief executive officer and the executive team is crucial to the success of the transition of the organization from an independent entity to its new home as part of a larger system. While the board owns the ultimate responsibility for the organization’s successful integration, as with most matters, the devil is in the details. Those details are most often in the hands of the executive leadership team.

During the process of acquisition/merger, communication with the board as to how its role will change generally falls to the chief executive, at times in conjunction with the board chair. It is critical that the CEO discuss the what, the how and the why.

In discussing the “what” of the role change from independent community board to a multitiered governance structure, CEOs should not hold back details regarding what that role is or will be. The change in the board’s role is sometimes seen as a loss of authority, or control at the local level. That is true to some extent. Conversations regarding the shift in roles should be discussed in a way that focuses on the value of the new role versus what is being lost.

One example might be the opportunity to shift time and energy previously spent on fiscal responsibility to quality, or the board’s role in addressing inequities and broader community health — often areas independent boards do not have bandwidth to engage in beyond high-level planning. The system CEO should be very intentional in supporting the local leadership to ensure their boards feel valued and heard. In other words, do not invite them to dessert only; make sure they are at the table for the entire meal.

How the board’s role will change is best addressed through actual board-specific activities. One opportunity for the CEO (pre acquisition/merger) is to create an example of how a board agenda will change under multitiered governance. Additionally, the CEO needs to work closely with the board chair on the framing of those changes as a win, not a loss. The system-level CEO might consider making him/herself available to participate in crafting the local board’s responsibilities to make them as rich as possible, while supporting the needed levels of governance.

Most importantly, the CEO needs to serve as the primary communicator of the “why.” The process of acquisition/merger can be likened to dating and marriage. Difficult conversations may be avoided so as not to “rock the boat.” This can lead to a very unhealthy marriage. Chief executives at the local level need to partner with their board chairs in direct and transparent communications to ensure that the board members stay mindful of why they chose this partnership and what they stand to gain, not what they perceive they have lost.

The Subsidiary Board

If the role of the executive leadership team is to provide an understanding of the new role of the subsidiary board within a newly affiliated health system and foster trust with the system, the role of the subsidiary board is to understand its new responsibilities and cultivate that trust.

Unfortunately, subsidiary boards often report a lack of clarity around their newly identified responsibilities and how they fit into the larger governance structure.

Subsidiary boards that do not fully understand their roles will govern the way they always have, which in this case means outside the boundaries of their newly established authority. The result? Governance quickly becomes inefficient.

For example, in multitiered governance, the responsibility and decision-making authority for setting financial targets and strategic direction are often the purview of the system board. Yet, we’ve seen many subsidiary boards continue to have finance and strategy committees. Such “mistakes” take valuable time away from the subsidiary board’s true areas of responsibility, which can lead to gaps in oversight, leaving the organization vulnerable to greater risk. These committee structures also require significant care and feeding, resulting in the use and expense of unnecessary resources.

Confusion around responsibilities and purpose can negatively impact board engagement as members no longer understand how their contributions provide value. In addition, misalignment and failure to focus on the right areas can produce tension between the boards and management teams, reducing their ability to effectively collaborate.

The first order of business a subsidiary board should undertake, then, is understanding how its authority has (or will) change within a multitiered governance structure. What are the delegated authorities from the system, and what authorities does the system retain? How have fiduciary duties changed?

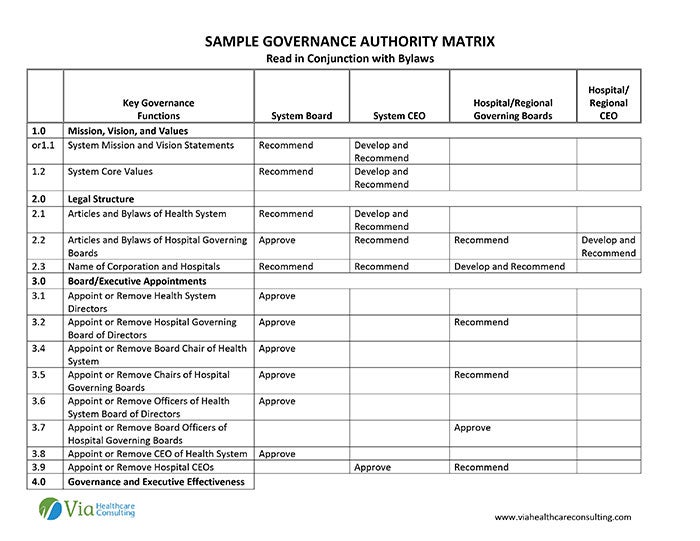

This information should be presented in the form of an authority matrix that outlines key governance functions in such areas as mission, vision, and values, legal structure, strategy, budget and operations and governance effectiveness for the levels of governance and executive management (e.g., system, regional, local). The authority should be described in plain language and written so that the boards can understand how to operationalize exactly what they are charged with accomplishing.

If the organization does not automatically supply an authority matrix, boards should request one — ideally before the affiliation takes place.

Understanding its authority, duties and responsibilities will enable a board to better understand the actual work it will be doing and how board operations will change. The agenda items at board meetings. Decision-making authority. Areas of priority. All will most likely change. Local hospital boards, for instance, often play a greater role in quality, community health and community benefit in a multitiered governance structure. Likewise, as we noted, local boards often relinquish their budgetary and financial authority to a regional or system board when there are multiple layers of governance.

Communication among boards is also essential in a multilayered structure. This includes across lateral boards (i.e., subsidiary to subsidiary) and from subsidiary to system. Boards within a system should, for example, understand the priorities and strategic matters of interest for a specific area or region for like boards. Standardized reporting that provides trended and comparative data across the various entities within the system can enhance the subsidiary board’s understanding of local performance in relation to system goals.

A subsidiary board should understand that it will be giving up some authority. Knowing this beforehand will help alleviate any resentment of new, streamlined authority and prevent small obstacles from growing into untenable situations. The role of a health care board is to consider the patients and community — and taking steps to make a healthy affiliation work is part of that role.

The System Board

As the governance body where the buck ultimately stops, the system board should fundamentally achieve a full understanding of the reserved, shared and delegated authority between it and the subsidiary boards.

Again, having the governance matrix is imperative to this understanding.

Beyond this fundamental expectation is the need for the system board to take a step back to consider the implications to governance as the system grows and becomes more complex. Boards often gain oversight of the full continuum of care, as growth often involves non-acute, ambulatory services. Oversight may be stretched too thin and resources strained. The goals and missions of these new organizations within the system will differ. Committee structures will need to be examined and redesigned.

The system board can dramatically influence the effectiveness of the health system’s complex governance structure by setting an example of being governance-focused and transparent across the boards. In this respect, communication with the subsidiary boards is key. Developing feedback channels with subsidiary boards is instrumental to understanding what is working well and what is proving to be an obstacle to effective governance at the regional or local levels.

One system that we work with requests a summary report of the subsidiary/hospital boards’ annual assessment of their performance (board self-assessments) to obtain an understanding of how the subsidiary boards are evaluating their own performance and experience. This system also has its communication team develop and distribute a bi-monthly newsletter electronically to all the trustees participating in governance across the system. This newsletter includes a high-level report on the system board’s most recent meeting and the issues it is dealing with.

Effective communication can also serve to align the goals and visions of the health system with those of the individual organizations.

System board members should consider their role as leaders and champions for other boards and board members across the system. This does not mean they should seek an outsized role for governance and invite the boards to go beyond their prescribed roles, but rather to be a “presence” at system-level meetings.

Effective Multitiered Governance

To realize the benefits of becoming part of a system, governance at all levels of the organization must be aligned and working in concert. Organizations joining or forming a system can be thought of as entering a “marriage” in which the boards must readjust expectations and learn their roles and responsibilities within the newly formed union for harmony. For the health system to be successful, these new roles and responsibilities should be clearly articulated and communicated throughout the various tiers of governance.

Without such alignment, there will be mistrust between subsidiary boards and the system board, hampering successful integration and overall system performance. When mistrust exists, subsidiary boards are often less likely to try to mitigate challenges or obstacles in the relationship or even support a continuation of the affiliation. We have seen such relationships suffer a long, expensive and needless death.

Governance within a multitiered system is complex. Setting and understanding expectations can address this complexity, create more cohesive governance and position boards to be their most effective.

Linda Summers, MBA, (lsummers@viahcc.com) is senior principal, Erica M. Osborne, MPH, (eosborne@viahcc.com) is principal and Karma H. Bass, MPH, FACHE, (kbass@viahcc.com) is managing principal at Via Healthcare Consulting based in Carlsbad, Calif.

Please note that the views of authors do not always reflect the views of AHA.