Board Meetings

How to Make the Most of Your Board's Time

Move beyond familiar methods to apply techniques that will hone in on forward-focused matters

By Steve Gordon, M.D.

Trustee Talking Points

- Health care boards face increasing pressures to use scarce meeting time together wisely.

- Even boards with well-managed meetings and prioritized agendas can feel challenged.

- Trustee morale declines when too much meeting time is devoted to lower-value activities.

- Organizations benefit when boards spend a majority of time on forward-focused matters.

Health care boards face increasing time pressures. Demands on boards’ time include expanding organizational scope, facing uncertain marketplace forces, addressing heightened demands for accountability and transparency, and implementing governance best practices. Absent lengthening or adding meetings, boards need ways to improve and sustain effectiveness to continue carrying out their duty of care. In addition to more familiar methods of meeting management and agenda planning, boards can apply techniques adapted from improvement science to governance.

Boards must use scarce meeting time together wisely, focusing on the organization’s future while providing perspective and making decisions to generate value for stakeholders over the long term. Boards are instrumental with regards to mergers, acquisitions, partnerships, service adjustments and similar matters impacting organizational mission, in addition to hiring the right CEO. A good rule of thumb is that boards should spend a majority of time on forward-focused matters.

Trustee morale declines when boards spend too much time on lower-value activities, such as receiving information (e.g., lengthy slide decks), reviewing administrative matters with questionable need for governance input, conducting work with the full board when a committee might address it more effectively, and acting as an audience to a dominant or disruptive voice when the majority of the board has reached a conclusion and is ready to move on. Maximizing time spent creating value requires a combination of management, prioritization and preventive efforts.

Manage Meetings Wisely

The pressures and complexities of today’s health care environment mean even boards with well-managed meetings and prioritized agendas can feel challenged, overwhelmed and demoralized. This feeling can especially be true when pressing issues of the day repeatedly mean trustees must table future-focused discussions. Trustees may hesitate to serve as officers or lead committees, or may resign in the face of competing time demands. Recruitment may suffer.

Effectively organizing and conducting board meetings are the low-hanging fruit of time management. For example: Consent agendas can be utilized to group routine actions and reports into a single time-saving motion. Many boards insist that staff limit presentations to a few slides emphasizing the action under consideration, the options and implications, and why board involvement is needed. Board agendas should indicate the allotted time and desired outcome for each item, such as a board vote, a straw poll, providing perspective to the CEO or shared learning.

In addition, trustees should expect one another to read all materials ahead of time. And trustees should view their meeting attendance as crucial to board effectiveness; absences should be explained. Finally, board chairs must be skilled at meeting facilitation, and staff must be attuned to their roles in supporting and participating in discussion. Written guidelines or standard processes for these basic functions help in maintaining and reinforcing meeting efficiency and also in orienting new participants.

Prioritize Agendas

Running meetings effectively nevertheless fails to create value unless the issues being addressed are instrumental to the organization’s future. Meeting organizers, typically the board chair and CEO, must prioritize agenda items and allocate time through the lens of strategic direction and risks. The link between the topic item and organizational priorities should be clear to all participants. Simply put, so what? Does the item need board action? Why? Can it be handled in the consent agenda, or is discussion needed? Can a committee handle the item with a recommendation to the board? How does the item relate to strategy? Has a new risk emerged or blossomed? Does direction need to be revised? Is more out-of-the-box, generative thinking needed to explore alternative scenarios?

Consistently curating a well-prioritized board agenda to drive organizational value requires close collaboration between the board chair, committee chairs and the CEO, along with input from the executive team and other trustees. Watch for trustee disengagement as a sign that time may be better spent on other matters.

Use Root Cause Analysis

Oftentimes boards rely on outside consultants to conduct comprehensive effectiveness assessments, especially when signs and symptoms indicate a more holistic and preventive approach is needed or included as part of periodic health check. Boards can also tackle effectiveness and efficiency using internal improvement expertise and working in alignment with other performance improvement efforts.

Improvement specialists begin by helping teams (boards, in this case) agree on the problem to be addressed, often by probing for implications to mission and barriers to achieving objectives. Specificity matters. What may initially be expressed as “we need more time to get through all our agenda items” might be reframed as “we are not devoting enough time to new risk areas such as cybersecurity and population health” or “our inability to attract younger trustees leaves a gap in our perspective of consumers and our perception in the community.” Exploring root cause analysis is essential, aided by improvement tools and techniques. Why does the situation persist? What has been tried before? Why didn’t that work? What additional information would be helpful?

This line of questioning can and should extend beyond board process and explore board composition, structure, leadership, and the flow of information between management and governance. These topics may be uncomfortable for some trustees, and conversation must be handled respectfully. Guided by your improvement specialist, eventually a shared picture emerges of a preferred future state, creative ideas begin to flow as to how that future state might be achieved, and a plan is formulated and implemented for testing new approaches and measuring impact. As part of a more comprehensive improvement plan, boards should adopt simple process or outcome measures for gauging effectiveness and efficiency, such as the number of pages in a board packet, the number of slides in board presentations, or the percent of total meeting time spent on future-focused topics.

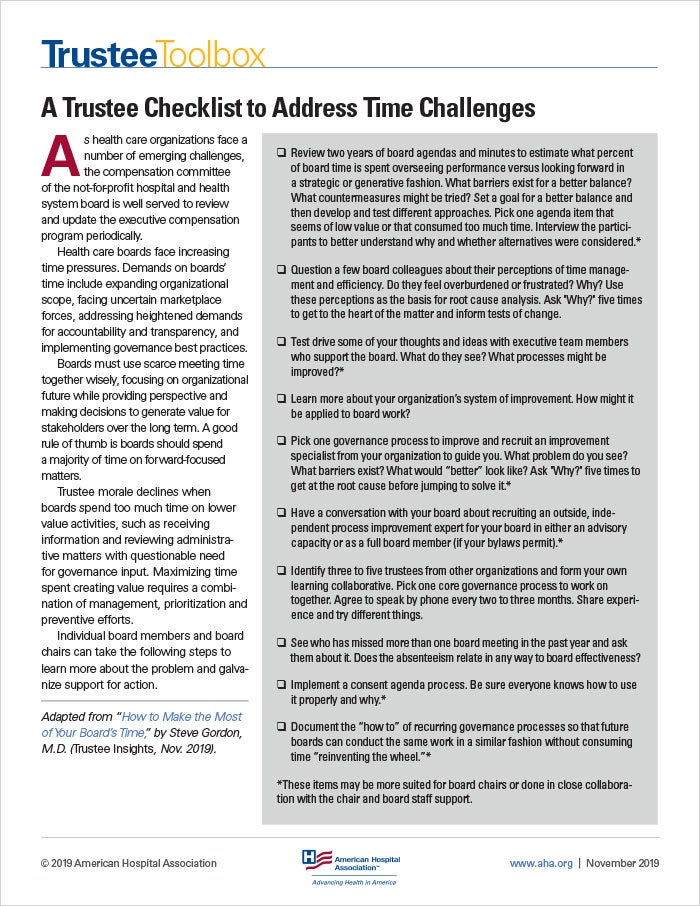

Trustee input and perception should be solicited as part of routine evaluation after each meeting. Improvement plans should have realistic timeframes for testing and evaluating changes, as well as accountability. Start small and secure quick wins. The sidebar "A Trustee Checklist to Address Time Challenges" (see page 2) lists a number of steps individual board members and board chairs can take to learn more, get started and galvanize support for action.

Trustee Takeaways

- Absent lengthening or adding meetings, boards need ways to improve and sustain effectiveness.

- Beyond more familiar methods, boards can apply techniques adapted from improvement science.

- Internal improvement specialists can help boards agree on the specific problem to be addressed.

- An improvement plan tests new approaches and measures impact within a realistic timeframe.

Lead by Example

Applying an organization’s system of improvement to governance itself benefits trustees and the organization as a whole. A recent survey by U.C. Berkeley researchers revealed more than two-thirds of U.S. hospitals now employ Lean or Lean-like improvement systems (though only 12% have reached a mature level of adoption). By working with internal improvement experts, trustees can learn firsthand about how the enterprise improves and become better versed in the tools and techniques of this important organizational function.

By “learning by doing” and “leading by example,” boards can develop experience and signal to the whole organization that the board is serious enough about continuous improvement to apply it to themselves. Taken together, these impacts can help build momentum, influence culture, and sustain longer term initiatives to reduce organizational waste and improve care quality, safety, satisfaction and operational performance. A recent white paper from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement identified understanding improvement system knowledge as a core board competency for effective governance of health care quality. The authors also identified available time as a top barrier facing boards today.

Time constraints are a growing challenge for health care boards. Board effectiveness and organizational performance benefit when boards are mindful of spending a majority of their time on high-value activities and have a plan in place to continually improve.