Board Meetings

Deliberate Decision-making and the Effective Board

Boards need to learn both how and when to make clear and appropriate decisions

By JoAnn McNutt, Ph.D.

Trustee Talking Points

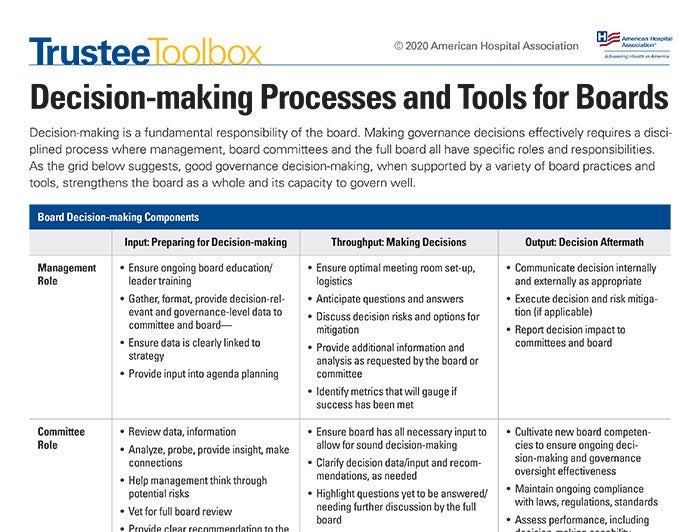

- For boards to make good and effective decisions, they must understand the decision-making process, which comprises input, throughput and output.

- Board composition is vital to good decision-making; diverse membership and points of view lead to better due diligence.

- A carefully considered decision-making authority matrix is helpful for choosing who will make the board decision.

- To measure the long-term value of its decisions, the board must determine what metrics it will use to hold itself accountable for the success or failure of its choices.

The hospital board is responsible for a variety of decisions that directly affect the organization’s long-term viability, from budgets and bricks-and-mortar planning to physician credentialing and senior executive leadership succession. Whether approving meeting minutes or determining key strategic priorities, the ultimate charge of the board is to make strategic and policy-level decisions.

In today’s environment of heightened accountability and risk, strong and effective health care board decision-making “muscles” are needed now more than ever. Today’s boards must go beyond checking all the good-governance boxes, and learn both how and when to make clear, ethical and appropriate decisions.

High-performing boards make decisions at the right time using the right processes. When we study boards that are struggling, we typically find that they missed the opportunity to make a decision. The most important example involves CEO and leadership succession. The board’s one employee is the CEO, who in turn employs the rest of the management team, thereby giving the board’s single hiring decision a global impact on the hospital or health system’s long-term success. For boards to make good and effective decisions, they must understand the decision-making process, which comprises input, throughput and output.

Decision-making Input

This initial phase of decision-making requires both qualitative and quantitative information. If the organization is deciding whether to merge with another health system, for example, qualitative input might include analyzing the impact of such a decision on the organization’s culture, taking into consideration which stakeholders it would most affect. Quantitative input would include legal due diligence, calculating the return on investment and considering other business reasons for the decision. These data must be in-depth, accurate, credible, relevant and complete, and it is management’s responsibility to involve the people most capable of gathering, strategically analyzing and packaging that information for the board audience. It is worth noting that it is the quality, not the quantity, of data that matters. Five pages of focused, strategic-level information and analysis will always be more relevant and impactful than 200 pages of data. Finally, input for decision-making needs to reach board members far enough in advance of board and committee meetings so that they can adequately review and prepare to discuss it. Any clarifying questions board members might have about input should be taken to the board chair and the CEO before the board convenes. The issue at hand can then be discussed at a higher, more strategic level during the meeting.

Decision-making Throughput

Management and the board should jointly determine whether the information gathered should be used as the basis for a committee-level or full-board deliberation. That choice underscores the importance of mutual respect and trust among all board members and the management team—another key ingredient to successful decision-making. Just as management entrusts the board to make sound decisions, board members must trust that management has given them the best information to make those decisions.

Board composition, therefore, is vital to good decision-making. Diverse membership and points of view lead to better due diligence if all board members are actively engaged in decision discussions. However, because different personalities can help or hinder the decision-making process, a skilled facilitator is critical—and that is the role of the board chair. He or she needs to make sure that all board members have the chance to be heard, particularly those who may not regularly speak up, in order to create an egalitarian culture of consensus-building. An effective board chair exercises good judgment, has a high emotional IQ, and the courage and ability to constructively guide the discussion back on course when necessary. Finally, the board chair also must consider whether there are any conflicts of interest related to a decision, which would then require board members with actual or perceived conflicts to recuse themselves.

Decision-making Output

The board must further consider the potential outcomes of each decision, managing risk and worst-case scenarios. For example, when a merger, affiliation or CEO transition occurs, how will the community or hospital staff react? All possible downsides of an important decision must be anticipated, and the board and management must present a united front, reaching consensus on how the decision will be presented to the rest of the organization and the community. A solid, agreed-upon narrative matters and must always be connected to the hospital’s mission, vision and values.

Determining the Who, How, When, Where and Why of Decisions

A carefully considered decision-making authority matrix is helpful for choosing “who” will make the board decision, whether it’s one of the board’s standing committees, the executive committee or the full board. That determination is typically organization-specific, while the “how” of decision-making (i.e., voting) tends to be situation-specific. The board also must clarify what type of voting process—simple majority, supermajority, unanimous, etc.—to use for each type of decision. Board members must consider the pros and cons of each voting choice. For example, will a simple majority vote be enough to convey the board’s support for a significant and weighty decision or would a supermajority or unanimous vote be more appropriate?

One of the most important elements of the decision-making process is the “when,” or the timing of a board decision. Boards that struggle with this aspect of decision-making often take too long to make a decision. A “gut check” may be the best determinant of when to make a decision, but the success of this approach relies on mutual trust among board members and the board chair’s skill in facilitating the right discussions at the right time. It also takes courage to call out concerns when board members rely on their “gut check” but may not have data to support what they know intuitively. While board meetings are where most cyclical and quarterly decisions are made, off-site retreats may be better for making significant, strategic decisions. Regularly scheduled executive sessions are best used when the board has sensitive issues to discuss.

Finally, the “why” of board decision-making requires a particular level of thoughtfulness. Board members should not hesitate to ask themselves and each other why they are contemplating a particular decision, and to analyze whether that decision is actually a governance matter or if it actually belongs to operations or physician leadership.

Continuous Improvement and Board Decision-making

To measure the long-term value of its decisions, the board must determine what metrics it will use to hold itself accountable for the success or failure of its choices. Each board committee can determine its own metrics, while the full board should analyze how well each step in its decision-making process is working. The board chair should routinely lead an open discussion in which board members and management talk about their roles and expectations for each other within their decision-making processes. Certainly, all boards can benefit from examining lessons other boards have learned and from successful boards’ best practices.

Ultimately, decision-making is the glue that binds all elements of board composition, culture, structure, information, policies, strategy and leadership. It is not a moment in time—it is a complete body of work. When organizational values are kept at the forefront in a codified board decision-making process, a positive ripple effect occurs that upholds the hospital’s purpose, and reinforces its leaders collective understanding of why what they do matters so much.