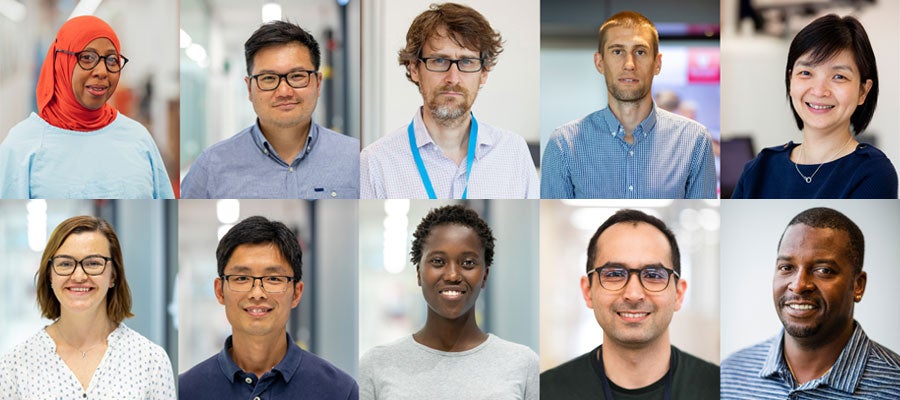

Diversity

“The Thing About Diversity Is …”

Debunking five misconceptions that derail diversity efforts

By Karma H. Bass and Erica M. Osborne

Diversity, equity and inclusion have become a priority in C-suites and boardrooms across the country due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionate impact on marginalized and minority communities as well as ongoing calls for racial justice. This is heartening because buy-in from the top is necessary to bring about meaningful change. However, buy-in alone is not sufficient. We have seen many diversity efforts fail because of misconceptions about what diversity is and what is necessary to achieve it.

Taking action

Governing boards may have good intentions around increasing their diversity, but unconscious bias or lack of understanding can lead to a defeatist attitude when recruiting efforts stall. Additionally, a “what more can we do?” attitude may emerge when the board isn’t able to retain a new member from minority communities.

In reality, there’s always more that can be done to achieve diversity of race, ethnicity, gender, age, expertise and experience on health care governing boards. It requires stepping out of our comfortable patterns and approaches. There are no simple solutions to addressing the racism that has pervaded our nation’s institutions for hundreds of years. To help boards persevere in this critical effort, even in the face of setbacks, we have compiled a list of reasons given for why a board’s efforts to diversify have stalled, with potential actions to get back on track.

Misconception

“Our community isn’t diverse, so we don’t need to be diverse.”

Action

Expand your concept of diversity.

Diversity, by definition, comes in many shapes and sizes. It isn’t just about ethnicity, race or gender, although those may be primary considerations. Diversity also includes sexual orientation, physical disabilities, military service, geographic location, education level, socioeconomic status, and more.

For some boards, the first step might be expanding the concept of diversity. Boards should take the time to ensure they have a thorough grounding in the demographics of the communities they serve — by all measures. Special attention should be paid to the needs and voices of underrepresented populations. The effort to diversify the board should include the goal of having the board’s composition reflect the community’s diversity, broadly defined.

To be representative of the community, a board must include members who understand the experience of marginalized communities. For instance, many communities are experiencing challenges related to food insecurity or housing instability, or both. The board might seek a person who has experienced these challenges or a representative from an outreach organization, such as United Way or the local food bank, who works with people experiencing such challenges. Understanding the experiences of these groups can provide board members with insights they would otherwise be lacking.

The American Hospital Association is partnering with the National Urban League and UnidosUS to match their affiliate executives to AHA member CEOs and governance leaders with the goal of placing these leaders on AHA member governance boards. To learn more, visit the AHA Trustee Match Program website.

Misconception

“We can’t find diverse candidates.”

Action

Expand your sources for locating candidates.

When boards say they cannot find diverse candidates to consider, we suggest rethinking the approach. Just as boards may have to expand their concepts of diversity, they also may have to expand where they go to find candidates and how to approach them. Professional associations for specific communities (i.e., African American, Latino) can be a good source to identify candidates who have business experience and may have served on other boards.

Some hospital and health system boards consult with their local community clinic or social service agency leaders or look to local business owners, who have developed trust and positive relationships with community members and have an in-depth understanding of their needs, to identify prospective board members. Others engage recruiting firms to assist them when more traditional approaches fail.

Misconception

“We have a diverse board member, but they aren’t really qualified.”

Action

Prioritize qualifications and diversity. Clarify the qualifications and skills sets being sought. Ensure ongoing education and development are available for all board members.

Prioritizing diversity over qualifications in the choice of a candidate is shortsighted and has the potential to lead to tokenism — adding diversity to comply with a policy, for example, rather than truly seeking experience and expertise that would serve the board well. This mindset sets up efforts to achieve diversity for failure. Diverse perspectives are essential, but so are qualifications and fit. It is incorrect to believe they are mutually exclusive.

To be successful in recruiting diverse and qualified candidates, boards need to clearly define which skills, expertise or experience are needed to provide effective oversight. This is table stakes to effective board recruitment because the entire board suffers when there isn’t clarity around what it takes to be successful as a board member. Any board member who lacks the appropriate skill set, experience or expertise will be less likely to meet the needs of the board regardless of their gender, race or other attributes.

Another misstep is when boards don’t provide the critical orientation, onboarding and ongoing education necessary for all board members to succeed. If board members appear unready for their responsibilities, the board should examine its own practices around board orientation, education and engagement rather than assuming it is a failure of any individual.

In our experience, there are always diverse, qualified candidates to be considered. It’s possible these individuals are just not part of the current board members’ social or personal networks. If your current process is not yielding the desired results, consider revising it to include the option to seek outside help, if necessary, in order to find the candidates that are the right fit both from a diversity and skills perspective.

Misconception

“Some populations don’t seem interested in serving on governing boards.”

Action

Expand the way board service is offered to the community.

One comment that we sometimes hear is that certain groups or cultures “do not value” board service. This sentiment, in itself, shows bias. While it may be true that some community members may not be accustomed to or familiar with traditional not-for-profit board service, this does not mean they do not value the service a board provides. Instead, it may speak to a lack of understanding as to how individual board service might benefit them and their communities. Because boards need diverse perspectives, it is incumbent on board recruitment efforts to include clear and effective explanations on the value of board service.

Successful and culturally appropriate recruitment strategies seek first to understand what a potential candidate’s community service interests may be and then show how board service addresses these. Boards may need to reframe how they explain the board’s role, its intrinsic rewards and how a board’s service is helpful to the community in order to attract the most qualified and diverse board members.

Finding a broader, more diverse pool of candidates may require providing more open access to consideration for board service. Members of minority communities have historically not had access to the powerful professional networks from which board members are traditionally drawn. Some boards are taking the step of posting their openings in a public forum and inviting applications.

The benefits of diversity are well worth the extra efforts it takes to clarify how one becomes a board member and to educate potential candidates about the board’s role in the health of a community. Taking the time to build trust and finding ways for all members to feel engaged in their role on the board will empower the entire board to take ownership for the health of the communities it serves.

Misconception

“We recruit diverse board members, but they don’t stay.”

Action

Examine board culture to increase inclusion and equity.

Another misconception is that members from diverse backgrounds are more likely to leave before their terms expire. If you believe your board is experiencing this, it might be worth looking at how your board does its work: Are your board practices and culture inclusive? The unspoken power dynamics of who feels welcome to speak and who remains silent are an issue of board culture that shouldn’t be overlooked when considering whether your board is truly diverse and inclusive.

If your board has disengaged board members, consider asking why they don’t participate more actively. This is a best practice for any disengaged board member, regardless of diversity considerations. Using the insights gained, determine if adjustments can be made to the boardroom culture and board experience.

Can meeting times be held in the early evenings to accommodate work schedules, or could the location of the meetings be shifted to a more central location where transportation is more accessible? Has the new board member received the introductions and orientation they need to feel comfortable in understanding the issues and engage in discussions? Has a mentor been assigned who can help answer questions and provide support as the new member navigates their new role?

Most importantly, do all board members feel comfortable speaking their mind? If board members of diverse backgrounds are invited to share their views, the entire board benefits while the new member is empowered. Can every board member look around the board table and see someone who looks like them? It’s not diversity if you have a single person from a minority community and expect that person to represent all minority communities.

Joining a new board can be challenging for anyone so it’s always a “best practice” to provide comprehensive board orientation and ongoing education and training.

In for the Long Haul

These suggestions represent just a handful of ideas to improve a board’s ability to recruit and retain diverse candidates. Addressing such misconceptions directly can help pave the way for achieving diversity goals. Additionally, these practices will help move all board members toward best practices in recruitment and board engagement. By clarifying the value of board service, what is expected of board members and how board members optimally engage with each other, the culture and effectiveness of the board will be enhanced for everyone. That, ultimately, is one of the many benefits of board diversity.

Of course, there will be stumbling blocks on this journey. Because it involves honest self-reflection and changing traditional approaches and practices, the experience will not always be comfortable. What’s important to remember is that this is a journey, not a destination.

Karma H. Bass (kbass@viahcc.com) and Erica M. Osborne (osborne@viahcc.com) are principals with Via Healthcare Consulting and based in Carlsbad, California.

Please note that the views of authors do not always reflect the views of the AHA.