Environmental Trends

Post-COVID-19 Future of U.S. Health Care

How boards can prepare for an evolving landscape

By Brian Fuller and Jordan Shields

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our nation over the past two years. The way hospitals led, and continue to lead, pandemic response in their communities demonstrate a fact many know to be true: No matter the tumult we have collectively experienced over the past century — be it a financial crisis, pandemic or war — our nation’s hospitals have risen to the occasion to protect and serve their communities over and over. At the same time, hospital and health system trustees are asking what the future holds for their organizations and how they can best prepare for success.

As hospitals work heroically to help bring this pandemic to an end, they also are building new competencies — largely around organizing and managing care, as well as developing the risk-based approaches to paying for health — in order to ensure their viability in a post-pandemic environment. Never before has a singular event led to such wholesale, functional and structural “new normals.”

The pandemic has been, and will continue to be, a catalyst that accelerates change further and faster than we have previously seen in health care. By understanding and anticipating these ongoing developments, trustees can help ensure their organizations successfully transition to this emerging environment. This article explores three such areas of fundamental change:

- Population health

- Cross-vertical competition

- Capital-driven modernization

These three areas will impact how health care in the U.S. is delivered and reimbursed. This article offers guidance to trustees as they lead their organizations through this transformation on behalf of the communities they serve.

Population Health

The events of early 2020 revealed the underlying risk inherent in U.S. health care’s dominant, fee-for-service (FFS) revenue model, which for a number of months in 2020, would have been more accurately described as NSNF, or no service, no fee. Amid non-emergent procedure suspensions, providers worked to respond to a global pandemic as formerly dependable revenue streams slowed.

FFS revenue has underpinned U.S. health care for more than 50 years. In 2019, despite all the “transformation” of the post-global financial crisis era, 94.9% of U.S. health care payment remained either pure or modified FFS. Long since the health care field declared the decline of FFS beginning in the 1990s, population-based payment models still reside at the margin.

The pandemic revealed a new phenomenon in FFS health care: Volume can be elastic and can be “turned off.” Costs, meanwhile, remain effectively fixed, creating challenges for providers. Even though the volume disruption experienced at the start of the pandemic lasted only a few months, it created significant financial repercussions and left providers looking to Congress for relief.

The transition to capitation and risk will not be costless. Major investments in systems, competencies and skills — like care management, network access, and risk management — will be required. Private and public reimbursement methodologies are advancing quickly. Some providers have already made significant strides to adapt. Boards should be asking their management teams to quantify these investments, as well as to objectively evaluate their organization’s ability to manage the transition from per-unit to per-life revenue. By having these conversations now, trustees can provide the leadership necessary to support management through this challenging transition and ensure that their organizations thrive.

Cross-Vertical Competition

A field-wide transition from fee-for-service to at-risk revenue represents a true transformation of health care financing. As in any field that has undergone fundamental revenue model disruption, efforts to demonstrate value and quality will ensue. Boards need to ask how their organizations are prepared for this challenge.

Many boards are already familiar with this dynamic as they are seeing pre-pandemic lines of demarcation that largely separated the financing of care from its delivery fading away. Payer and provider incursions into one another’s traditional service areas are an increasingly common board room topic and one that will only become more prominent as population health and risk-based payment models grow.

Providers and payers alike are busily reassessing their visions and value propositions, charting their mission-driven futures in a new, at-risk revenue environment. These assessments are centering on a primary question: “Who is the optimal organizer and manager of the care delivered to (and thus cost incurred by) a patient or population?” The answers we are hearing from both parties, naturally, have been: “We are.”

As in other areas discussed here, cross-vertical competitive changes were happening before the pandemic. Organizations like Kaiser Permanente developed truly integrated provider-payer models that are not structured around FFS architecture. At the same time, payers were moving into care delivery, with the most notable example being UnitedHealth Group’s Optum Care, the largest network of employed physicians in the U.S. Providers also crossed the imaginary line, selectively participating in risk products through Medicare Advantage, undertaking nascent forays into direct contracting, and pursuing combinations to better organize and manage care. Trustees should be ready for the same drivers of change — insurance dislocation, strained state and federal budgets — to escalate competition as we move past the pandemic.

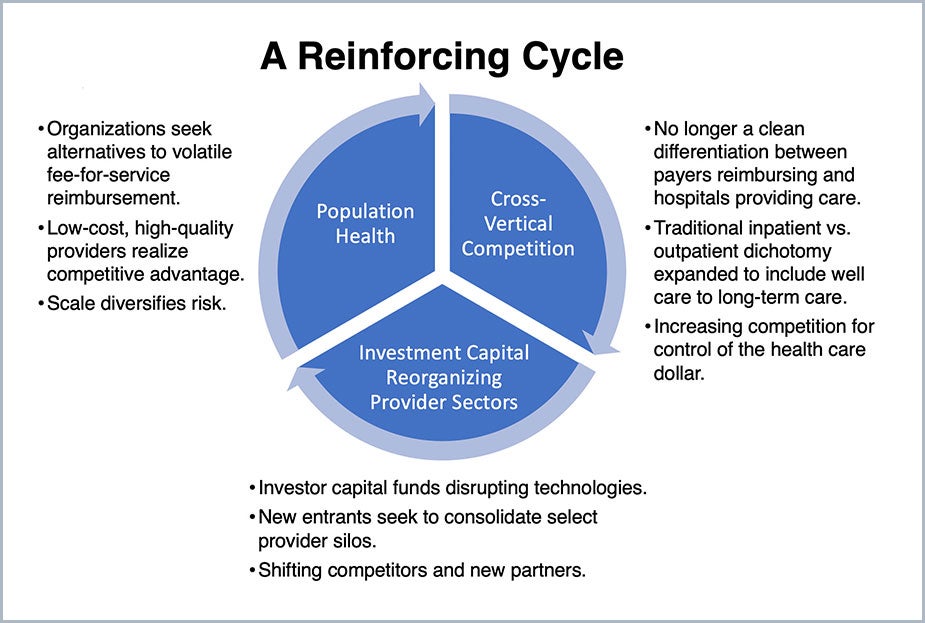

Figure 1. A Reinforcing Cycle

Source: Juniper and PYA

Boards should require their organizations to define how they will meet the health needs of their communities in a more fluid and competitive arena. A disciplined assessment of an organization’s ability to thrive in the evolving health care field has never been more critical.

Investment Capital Reorganizing Provider Sectors

Given the evolving payment and competitive landscape, hospital and health system boards need to take the time to understand the implications of investor activity and what that means for their organizations. Before the pandemic, unprecedented sums were flowing into health care-focused private equity funds which, in turn, flowed into all health care sectors, most notably services, at sharply accelerating rates. Private equity investment in health care rose seven times from 2009 to 2019, and health care services accounted for almost half of the total. Some hospital systems have embraced this trend with undertakings like Ascension Ventures and Baystate Health’s TechSpring investing in health care advances. At the same time, many boards watch the capital flows from afar without assessing the implications for their organizations.

The pandemic slowed private equity activity across industries in the first half of 2020, hitting health care particularly hard. That said, health care services fared relatively well, increasing their share of the total amount invested to 50% through June 2020. Forecasting private equity health care services inflows is difficult, but we anticipate continued investor interest. Opportunities abound for private equity to succeed by investing in operations and applying technology-driven efficiencies, and by building scale.

While opinions on private equity in health care may vary, there is little doubt it is here to stay … and will grow. These types of investments will continue to disrupt the field by accelerating spending on new IT-backed solutions and by creating scale to support the holistic delivery of care. Trustees must determine their view on private equity and its implications for their organizations, as it is real, and seeking “value creation” opportunities are seemingly everywhere.

Bold, Collaborative

Approaches for Change

The events of 2020 made it clear that the FFS business model that has survived for so long is unlikely to see us into 2030. In all of the areas discussed here — payment, care delivery, structure — boards must undertake comprehensive

introspection and develop bold approaches, to ensure that their organizations emerge more resilient and thrive in the future.

Trustees need to anticipate these changes and position their organizations for success, often by working with new partners. This change may come more easily for larger, scaled health care networks and organizations with access to capital. Do such realities portend the end of the independent hospital or physician practice? No. Does the change require even more creative and collaborative approaches? Yes. Those that succeed will do so based on their ability to create and demonstrate differentiation to their communities every day. To achieve this, some may pursue partnership strategies that allow them to access scale and network efficiencies while others will seek to build these capabilities.

The challenge for trustees today is to understand how their organizations meet market circumstances and fit into a changing field. Thoughtful and proactive planning will set U.S. providers on the road to post-pandemic success.

Brian Fuller (bfuller@pyapc.com) is a principal with PYA and leads the firm’s strategy consulting practice. Jordan Shields (jshields@juniperadvisory.com) is a partner with Juniper Advisory.

Please note that the views of authors do not always reflect the views of the AHA.